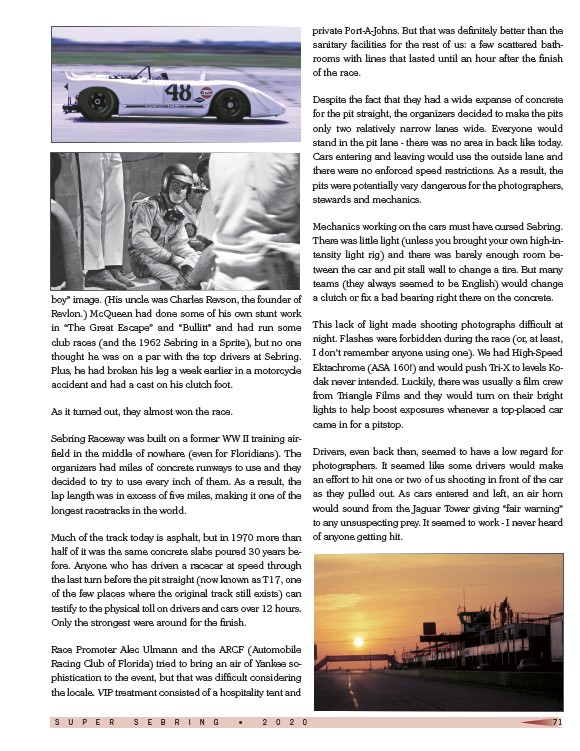

boy” image. (His uncle was Charles Revson, the founder of

Revlon.) McQueen had done some of his own stunt work

in “The Great Escape” and “Bullitt” and had run some

club races (and the 1962 Sebring in a Sprite), but no one

thought he was on a par with the top drivers at Sebring.

Plus, he had broken his leg a week earlier in a motorcycle

accident and had a cast on his clutch foot.

As it turned out, they almost won the race.

Sebring Raceway was built on a former WW II training airfield

in the middle of nowhere (even for Floridians). The

organizers had miles of concrete runways to use and they

decided to try to use every inch of them. As a result, the

lap length was in excess of five miles, making it one of the

longest racetracks in the world.

Much of the track today is asphalt, but in 1970 more than

half of it was the same concrete slabs poured 30 years before.

Anyone who has driven a racecar at speed through

the last turn before the pit straight (now known as T17, one

of the few places where the original track still exists) can

testify to the physical toll on drivers and cars over 12 hours.

Only the strongest were around for the finish.

Race Promoter Alec Ulmann and the ARCF (Automobile

Racing Club of Florida) tried to bring an air of Yankee sophistication

to the event, but that was difficult considering

the locale. VIP treatment consisted of a hospitality tent and

private Port-A-Johns. But that was definitely better than the

sanitary facilities for the rest of us: a few scattered bathrooms

with lines that lasted until an hour after the finish

of the race.

Despite the fact that they had a wide expanse of concrete

for the pit straight, the organizers decided to make the pits

only two relatively narrow lanes wide. Everyone would

stand in the pit lane - there was no area in back like today.

Cars entering and leaving would use the outside lane and

there were no enforced speed restrictions. As a result, the

pits were potentially very dangerous for the photographers,

stewards and mechanics.

Mechanics working on the cars must have cursed Sebring.

There was little light (unless you brought your own high-intensity

light rig) and there was barely enough room between

the car and pit stall wall to change a tire. But many

teams (they always seemed to be English) would change

a clutch or fix a bad bearing right there on the concrete.

This lack of light made shooting photographs difficult at

night. Flashes were forbidden during the race (or, at least,

I don’t remember anyone using one). We had High-Speed

Ektachrome (ASA 160!) and would push Tri-X to levels Kodak

never intended. Luckily, there was usually a film crew

from Triangle Films and they would turn on their bright

lights to help boost exposures whenever a top-placed car

came in for a pitstop.

Drivers, even back then, seemed to have a low regard for

photographers. It seemed like some drivers would make

an effort to hit one or two of us shooting in front of the car

as they pulled out. As cars entered and left, an air horn

would sound from the Jaguar Tower giving “fair warning”

to any unsuspecting prey. It seemed to work - I never heard

of anyone getting hit.

�� �� �� �� �� �� �� �� �� �� �� �� �� �� �� �� �� �� �� �� 71